Tatreez: Weaving Palestinian history

Published in The NB Media Co-op

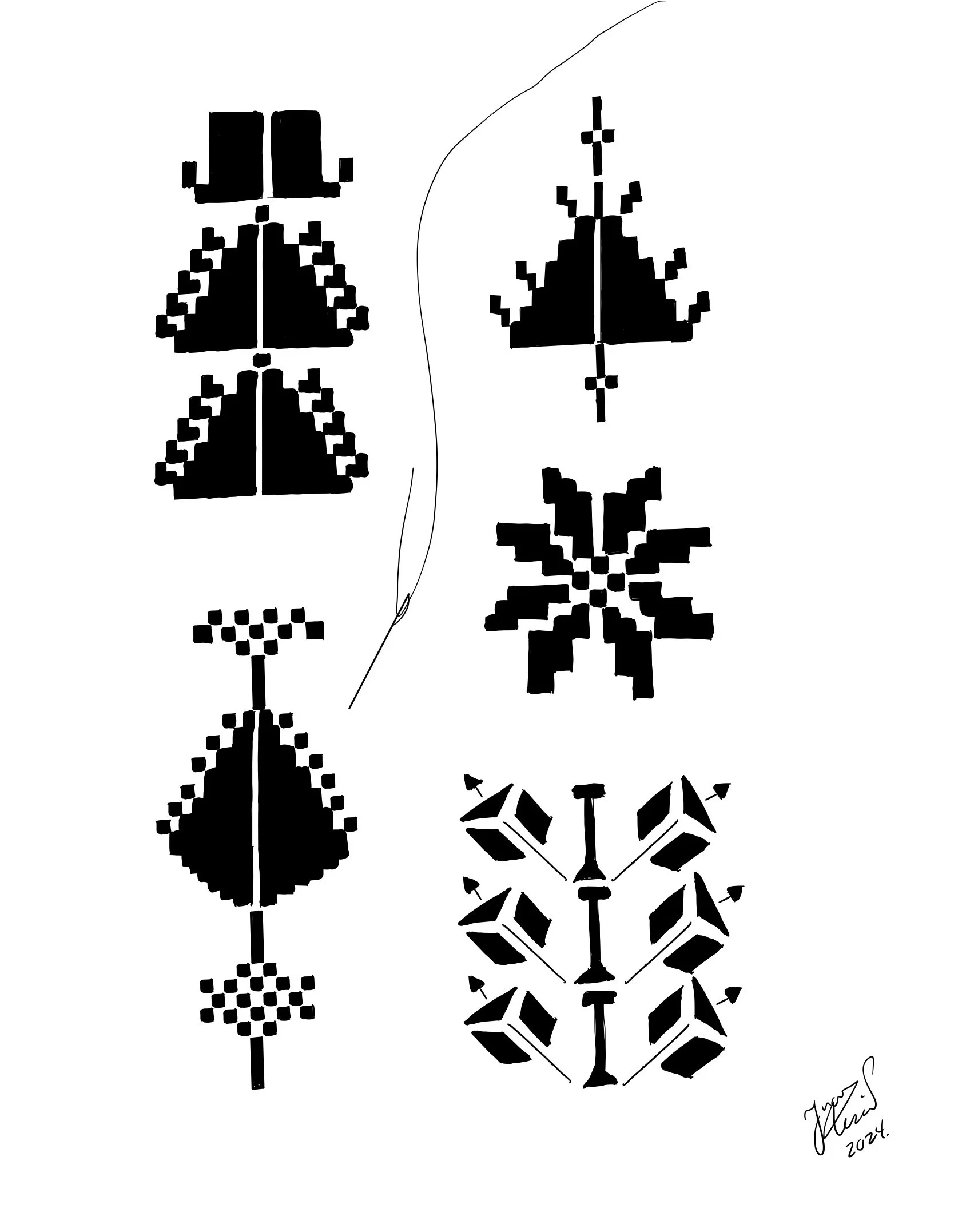

(*artwork: ‘Tatreez motifs’ drawn by Incé Husain. Top left: cypress tree from Beer Sabi; bottom left: cypress tree from Gaza; top right: cypress tree from Ramallah; middle right: Bethlehem moon; bottom right: coffee bean from Gaza.)

The Palestinian thobe fills my phone screen. It is black, originally indigo-dyed. It flares with orange, red, and jewel-coloured embroidery. The chest-piece is laden with triangles, zigzags, and flower-like motifs in an intricately ordered, occasionally asymmetrical, geometry. The front of the skirt bursts with a panel of appliqued squares bearing star-like motifs. The sleeves and sides are rich with greens, blues, and pinks that twine into branch-like patterns or descend in diamonds. The back is streaked with orange panels that border arching embroidery climbing nearly halfway along the skirt. In its entirety, the thobe is mesmerizing in the heaviness and vibrancy of the embroidery, handmade in 1920 from the village of Al-Masmiyya al-Kabira or el-Na’ani in historical Palestine.

Neither of these villages exist anymore, ethnically cleansed by Israel in 1948. The thobe lay in the British museum from 1989 to 1991, and can be seen online at the British museum’s official site.

Baraa Abuzayed, an embroiderer and PhD student in cultural studies at Queen's University, learned that three of her grandparents were displaced from the village where this thobe was made. She began recreating the thobe to accompany her Master’s thesis, in which she argues that the creation of thobes is inseparable from Palestinian survival.

“The village that this thobe comes from, it does not exist on a map, it is no longer there. But that thobe exists and it exists from that place, so that place does still exist through material history and through people who come from it,” says Abuzayed. “I recreated it saying that thobes have the power to represent and to give meaning and give life to places and to land that was stolen.”

The needlework on the thobe is “tatreez”, traditional Palestinian embroidery distinguished by unique motifs that embody Palestinian culture, history, and resistance. Abuzayed embroiders the thobe at a speed of a hundred stitches every minute and twenty seconds; the thobe’s chest-piece has 45,000 stitches, and the back panel has 55,000 stitches. She began the work under the mentorship of Samia Ayyash from The Thobe Project, who teaches the historical process of thobe-making - from cutting the fabric, to embroidering, to assembling.

“I felt like I needed to touch it, to feel it, to be able to understand how all of this is created, how all of this is manifested,” says Abuzayed of creating the thobe for her thesis. “I felt like, to be able to understand what I’m researching, I had to create it. When I was seeing all these thobes in front of me just as a picture (it wasn’t enough).”

Abuzayed and her siblings first learned tatreez from their mother at the age of ten. Though the practice of tatreez is traditionally passed on from mother to daughter, Abuzayed’s mother had taught herself while doing a university dissertation on the Palestinian wedding.

“(Tatreez) was the first thing she taught us,” Abuzayed says of her mother. “We would always embroider together and whenever we had occasions to give out gifts, we would create a piece. A lot of the pieces I created when I was young I don't have, because I gifted them.”

Abuzayed decided to pursue research on tatreez in her fourth year of undergrad, when she had taken a global development course that discussed basket-making as an example of collective community work. This moved her; she felt a synchrony between the essence of basket-making and Palestinian embroidery in its collectivity and resourcefulness. She emphasizes that she interpreted every course she took through the lens of Palestine, and always felt a pull to researching Palestinian history and culture.

“Every course I had, I felt like I could easily relate it to Palestine,” says Abuzayed. “For me, Palestine is the epitome of every single topic that we can think of. It covers feminist issues, development issues, politics, art, liberation - it covers it all’.

While in undergrad, Abuzayed began teaching tatreez workshops at Western University, introducing people to its form and meaning. She opened each workshop with a presentation detailing the political significance of tatreez. With presentation slides lush with thobes from major cities and tatreez depicting villages lost to Israeli occupation, she explained the resistance inherent in their preservation through embroidery.

“(Tatreez) symbolizes so much more than just a motif. Because the patterns, especially when the patterns start to symbolize places that no longer exist on the map - that’s when you know that it's something that needs to continue to be remembered and taught. It’s resistance knowing it and learning it.”

She also shared the “Intifada Dress” . This thobe emerged during the First Intifada, a six-year Palestinian uprising from 1987 to 1993 against the Israeli occupation. In 1967, the Palestinian flag had been banned by Israel; women began to embroider it into thobes during the uprising.

“Women were embroidering the flags on their clothes,” says Abuzayed, “and the dome of the rock. They were also embroidering guns, they were embroidering slogans, and things like that. The Intifada dress is a big one.”

Aimed towards those who are new to embroidery, Abuzayed’s workshops provide 14-count and 11-count fabric that easily shows the holes in cloth where stitches will be made. She shares motifs from the book Palestinian Embroidery Motifs: A Treasury of Stitches from 1859-1950. Learners select a motif, photograph it, and begin to go through the workshop, with Abuzayed attending to each group to teach the stitches. Some learners would even ask Abuzayed for patterns that came from specific Palestinian villages, expanding her resources for motifs.

For future workshops, Abuzayed hopes to show a video of herself stitching, which may help learners pick up cross-stitch. She is running a workshop in London, Ontario on February 8th, and a workshop at Queen’s University on February 15th (details will be posted here closer to the date).

“We used to host multiple workshops within a semester, and my sisters would also come and help me teach. It was nice because a lot of people would get so into it and they would complete motifs,” says Abuzayed. “It’s lovely to have people come and not be scared to try.”

Some of the most common tatreez motifs are cypress trees and the Bethlehem moon.

Abuzayed calls the Bethlehem moon “the most famous”. It shows a cross that unfurls, star-like, into eight cross-stitched wisps.

Cypress trees show a symmetrical, elongating motif that branches into repeating patterns framing the figure of the tree. Abuzayed shares that these motifs reflect the variety of cypress trees in Palestine, with unique tatreez arising from different cities. She shares examples of cypress tree tatreez from Gaza, Beer Sabi, and Ramallah.

The Gaza cypress tree starts with a checkered pattern that gives way to a triangle that grows then slims as it rises, its edge lined with small squares; the Beer Sabi cypress tree is a series of stacked triangles bordered by arrow-like patterns; and the Ramallah cypress tree begins from a small cross that rises in a triangle and narrows into wisps.

Abuzayed says her favourite motif is the coffee bean from Gaza. It features a stalk that sprouts leaves made of parallelograms and triangles. She says that her grandmother had a thobe from the early 2000s with sleeves embroidered with the coffee bean.

“It’s one of my favourite motifs,” says Abuzayed. “I created it so many times over and over again. I kept creating it, gifting it to people, making it as a bookmark.”

Though tatreez today is rich with colour, Abuzayed says that traditional tatreez was done in shades of red. Tatreez threads were originally hand-dyed with sumac, a spice drawn from the dark red berries of sumac plants indigenous to Palestine. As geopolitics shifted, DMC threads from France - cotton and multicoloured - were imported into Palestine and replaced the tradition of dyeing threads.

Traditional tatreez also differed in its process. Today, waste canvas is used to embroider tatreez on cloth. A fabric studded with holes, waste canvas is placed on top of the cloth to be embroidered to allow easier stitching, and is removed when embroidery is finished. Historically, tatreez was done with even-weave fabric, which has distinguishable holes for cross-stitch. Abuzayed adds that fabric was never wasted; each piece was used for a thobe.

“‘Our ancestors were very resourceful,” says Abuzayed. “Every single piece that they cut would be used for the thobe. That was something that was very interesting for me and that was something that I tried to replicate (in my thobe).”

In our increasingly technological world, tatreez has begun to emerge in digital form. Mugs, coasters, shirts, and other paraphernalia can be found with tatreez motifs digitally printed on them, expanding the scope of accessories that tatreez traditionally encompassed.

Abuzayed has mixed feelings about digital tatreez. She acknowledges that digital tatreez opens the craft to those who can’t embroider, but also feels that it distances tatreez from its original meaning and context.

“I don’t like (digital tatreez) that much to be honest, because it does remove its original meaning from the artform. That’s what I think. It does remove its original context and its original form that it used to be - on dresses, on pillowcase, on napkins, and on headpieces. The fact that that’s not done much is kind of sad,” says Abuzayed. “But I don’t blame the fact that people want to do (digital tatreez) because it’s one way that they want to feel closer to home and to Palestine. Especially when you don’t know how to embroider, it’s a way to hold something close knowing that it’s a part of your heritage.”

As global awareness of Palestine grows, there has been a resurgence of tatreez across the world. Activists who feel strongly about human rights embrace tatreez as a form of solidarity with Palestine, investing time to learn its significance and create it themselves. Tatreez artists are creating new patterns to capture current moments in history, embroidering motifs such as Handala or the watermelon. Handala is a drawing of a young refugee with his hands clasped behind his back; created by cartoonist Naji al-Ali in 1969, it is a symbol of Palestinian defiance. The watermelon - bearing the black, white, green, and red colours of the Palestinian flag - emerged as an emblem of resistance when the Palestinian flag was criminalized by Israel.

Digital tatreez by graphic designer Maya Amer went viral on Instagram last year. It featured a chest-piece of a traditional thobe recreated in green, yellow, red, pink, and gray; each stitch depicted a Palestinian who had been martyred from October 7th to October 31st. Green stitches depicted women, red stitches depicted girls, pink stitches depicted boys, yellow stitches depicted men, and gray stitches depicted those that could not be identified. The piece flares with red and pink.

“I think that's very cool because eventually, these designs will be archived and they'll be used,” says Abuzayed of the new motifs. “I saw the watermelon being embroidered - marking, again, a resurgence to the struggle, and towards resistance and liberation.”

In the wake of the current violence in Palestine that has exceeded a hundred days and 27,000 deaths, Abuzayed gravitates to tatreez as a way to calm her mind while still representing Palestine, its memory, and its continuation. She recalls feeling powerful when she first began working on the thobe for her Master’s thesis; it filled her with a deep connection to the ancestral homeland her family is denied.

“Embroidery has become part of what I do,” says Abuzayed. “It was such an amazing feeling just knowing that I was creating something for myself, but also something for my family, and to teach them about it, and to bring something closer to home that comes from the home that we are denied. That feeling alone gave me so much power.”

Abuzayed invites everyone to try tatreez. She considers it “very important” that people show interest in learning it and internalizing its power.

“Take time to understand the context of tatreez, that it’s very important to Palestinians, and its existence is optimal for Palestinian survival,” says Abuzayed. “Learn the motifs, learn about them - it will never die that way. And it hasn’t, for hundreds of years.” ♦

A version of this article appeared in The NB Media Co-op on February 11th, 2024:

https://nbmediacoop.org/2024/02/11/tatreez-weaving-palestinian-history/

*NOTE: on February 5th, 2024, the following sentence was changed:

She is running a workshop at Western University on February 7th.

The sentence was changed to:

She is running a workshop in London, Ontario on February 8th, and a workshop at Queen’s University on February 15th (details will be posted here closer to the date).