“Grounding: States of Gender”: Persian calligraphy documents memoir of womanhood in Iran

Published in Antler River Media Co-op

Republished in The Socialist

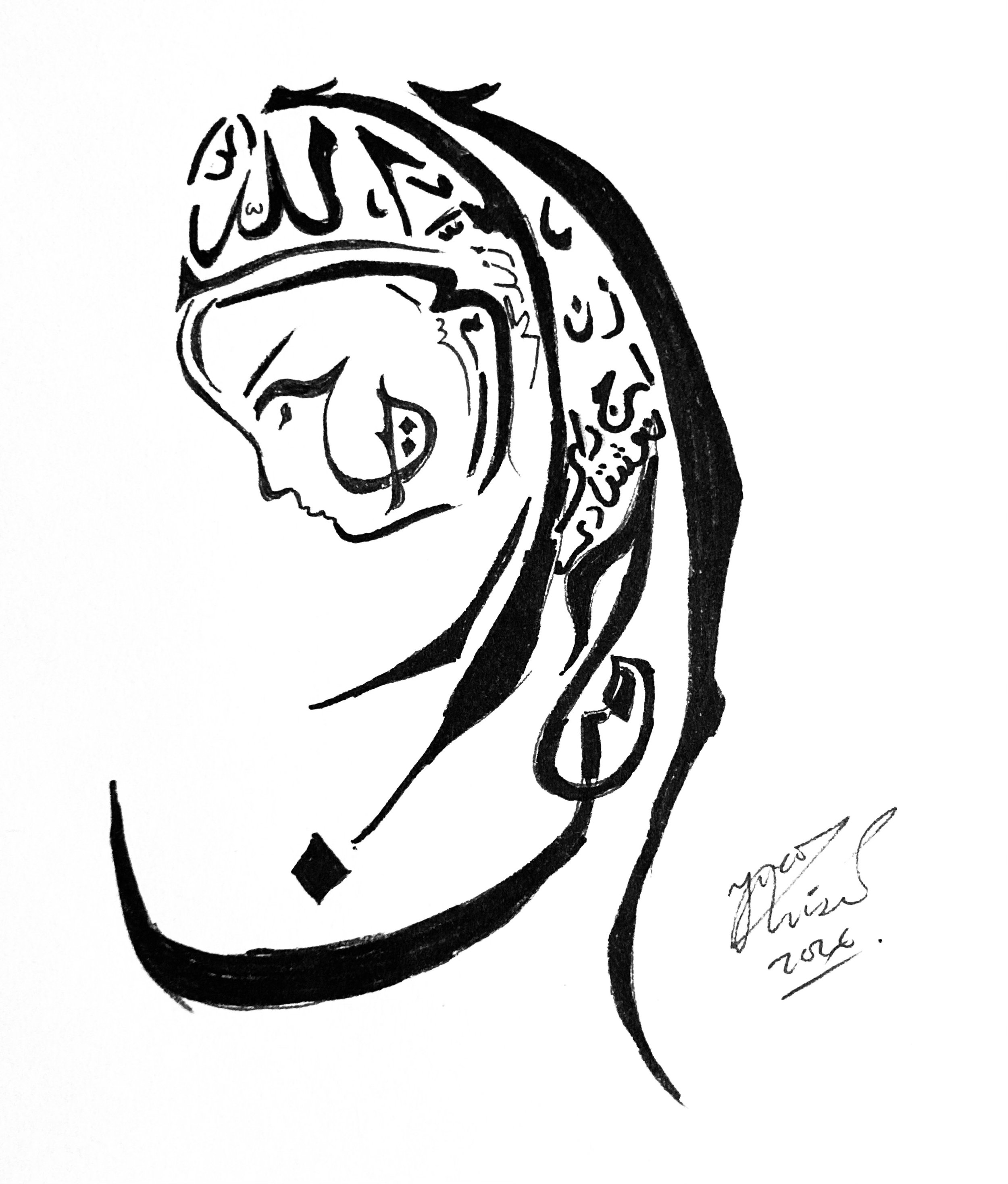

(*Artwork by Incé Husain)

“What are the ways in which gender — our gender as women — has actually conditioned our life?” asked Iranian artist Gita Hashemi, introducing her performance Grounding: States of Gender at Western University’s John Labatt Visual Arts Centre on January 8. Curated by Soheila Esfahani, the exhibit will be displayed at the artLAB Gallery until January 29.

Grounding features Persian calligraphy in red and black ink that tells the story of a woman in Tehran named Zahra. The swaying script is written on twenty-two scrolls that cover the gallery walls, circling audiences from all sides. Live-streamed footage of Hashemi writing the calligraphy — on hands and knees, with ink and paintbrush, the letters curling, flaring, flowing — is projected on the gallery floor. Evocative audio blares in the gallery: air-splitting ululations that mark “when the female voice becomes public”, a rush of men’s voices, women’s haunting and insistent whispers.

The words in the calligraphy are Zahra’s. They emerged through months of email correspondences with Hashemi where Zahra wrote about memories that mark her reflections on womanhood. Their discussions were intimate, revealing, and healing.

“We had to think about feeling — what is that feeling of childhood? — and visit all of the difficult and traumatic memories that are necessary,” said Hashemi. “What you see here is a documentation of that conversation.”

Zahra’s writing is raw. It documents graphic physical violence, harsh isolation, a fracturing self, cycles of tenderness sought and denied. Her body is explained as a site of carnal curiosity, fear, and submission. Her life — school, family, lovers, interrogation during the Iranian Cultural Revolution of the 1980s — is articulated through the lens of how gender has stalked her psyche.

“Gender grounds us in a set of relations outside our direct control. ‘States of gender’, for me, points to the fact that, although it is assigned, it is also in flux and can go through different states. At the same time, ‘states’ evokes the involvement of political systems in the experience of gender,” Hashemi said. “The title [Grounding: States of Gender] points to the foundational role of gender, which is itself a construct, in the construction of our identity, socio-economic status, and life experiences.”

Hashemi emphasizes the universality of Grounding. Though recounting the story of an Iranian woman, the concept of the performance arose as Hashemi contemplated the subjugation of women across the world.

“There is the man who is now president [Trump] saying “grab [women] by the pussy” and the over-exposed image of an imported made-up doll standing beside him. There is the campus rapist walking free, and the radio host acquitted of sexual assault. There were Pussy Riot in Russia, masses of women in rallies against rape in India, and Women’s March on Washington. There is the Islamic State, and here, in the “west,” is the state of poverty that increasing numbers of women are pushed into, courtesy of neo-liberalism and politics of austerity,” writes Hashemi. “Wherever we are located geo-politically, gender writes us. Gender writes on the body. It is the most pervasive marker of the individual and the social body. It defines us in the most intimate ways and in the most intimate spaces. It conditions our interaction with the world and our place and power within it. In a gendered state, there is nothing neutral about gender, nothing given, nothing natural.”

Hashemi explained that transcribing Zahra’s story in Persian calligraphy, on wall-sized parchment, resists convention. She described Persian calligraphy as a revered part of Iranian culture that has been dominated by men; the language is formal, focused on poetry, sacred texts, and sealed within manuscripts. Zahra’s story — written by a woman, calligraphed by a woman, in language that is colloquial, intimate, and profane, with lettering amplified to monumental scale — breaks these norms. It practices a bold equality of form, craft, and content. With this delivery, a silenced voice rises.

“There has not been space for women’s stories,” said Hashemi. “Some of [the text] is pretty intense to read and think about because there are stories of violence and, at some point, rape and all the various kinds of difficult experiences that women often have in patriarchal societies, including here.”

In traditional calligraphy, black ink is used for the main text while red ink might signify chapter titles or opening words. As Hashemi transcribed, she shifted from black to red ink when she read parts of Zahra’s story that viscerally marked her.

“As I’m writing the text and I’m finding that I’m physically reacting, emotionally reacting, to some of the text that I’m writing, I switch the color from black to red, highlighting those passages where I’m finding those reactions.”

Hashemi said it was crucial to livestream her transcribing of Zahra’s story. It ensured that the story was witnessed as it was created, synchronizing audiences to the labor of delivering Zahra’s narrative. The original livestream was created over eight days at Carleton University. Hashemi didn’t have Zahra’s full text when she began transcribing; their correspondences were ongoing, and Hashemi transcribed new text almost as it came. Two scrolls in the exhibit remain blank. They signify that other stories are yet to be written, and that Zahra’s story is not fully contained in Grounding — it precedes and outlives the performance.

“It was important that it be livestreamed because then it cannot be taken back and it cannot be censored in any way.”

For non-Farsi speakers, English translations of Zahra’s story are printed in folders. They lie in the gallery’s alcove on a small table surrounded by cushions. Translated by Hashemi and her collaborators, the translations are meant to “open a window to the world inside the work.” Hashemi refrained from providing English translations in the performance itself.

“This work could only be done in Persian and could not be subtitled in English because I think it’s important that the specific content should not be translated for consumption. You need to do some labour to access it. To get it, you actually need to sit down and read it and do some of the labour of contemplating a world, a cultural context… to reach your own conclusion of the work,” said Hashemi. “Translation is always a process of loss…Obviously, many culturally specific things remain opaque. That’s okay. As an audience, we need to get used to the discomfort of not getting it all. It’s a colonial impulse to expect that we can look at something that is culturally remote from us and fully occupy it.”

Grounding was completed in 2017. The #MeToo movement and #WomanLifeFreedom protests in Iran followed, a trail of dissenting stories echoing the harshness in Zahra’s. Today, Hashemi feels a tie between her work, current protests in Iran, and ongoing genocide in Palestine. She wore a black keffiyeh to the exhibit’s opening night at Western’s gallery.

“I am standing here fully aware that today and in the past few weeks there have been more protests in Iran. And I want to acknowledge that today is day 824 of Israel’s genocide in Palestine and year 77 of the occupation. As a minority, as a racialized person, an Iranian, I am very aware of the fact that any work that I do as an artist carries that history of colonization, trauma, political turmoil. All of that is very complete, heavy, and inside of however polished that the work looks,” Hashemi said. “As an Iranian witnessing the events in Palestine and Iran, I’m obviously concerned and affected. I think the ties between the work and the events are pretty deep even if a little less transparent than we might expect. The same patriarchal structures that drive colonial violence and social oppression also uphold gender constructs. Trump banned gender re-assignment treatment at the same time as he signed the increased military aid to Israel during a genocide. The Islamic Republic of Iran is quite adamant in maintaining gender binary as it is in suppressing political dissent.”

Hashemi penned a letter addressed to “Canadians of Conscience” that describes Iran’s cyclical history of revolutions and how to take action in the current moment. She writes:

We must demand that Canada end debilitating economic sanctions against Iran that have created rampant black markets for necessities of life. We must firmly stand against the brutality of the IRI against Iranians. We must speak out against the US agenda of regime change and the threats of military intervention. We must refuse to accept that the only choice for the Iranian people is between foreign occupation and iron fist repression.

***

Iranian graduate students Dalia, Salma, and Ebrahim visited the gallery for an hour. They relate to Zahra’s story and laud the bravery of Grounding.

“It’s a very sad story. I can literally relate to everything that she was saying. I can say that I’ve seen people who are experiencing the same thing,” said Salma. “That was very bold of her to describe it like this. I think it was disturbing for me to read but I am not regretting that I read it.”

Dalia resonates with the themes of internalized shame threaded throughout Zahra’s story. She describes the cultural weight of the Farsi word bi-âberu. It translates directly to “shameless” or “no dignity”, but the gravity of the word — and the way it hounds women in Iran — has no cultural parallel in English.

“There are words in Farsi that have a different weight. Shameless, no dignity — it’s something that we’ve been hearing over and over again in Iran and as a girl. That just has a heavy weight. If your family tells you that you made them — or that you lost — dignity or you’re shameless, it’s a heavy thing for someone to hear.”

Dalia is familiar with stories of Iranian women “accepting their fate” in forced marriages. Their intimate lives are dominated by their husbands. They might bear children they don’t want, provide intimacy they find distasteful, and succumb to all pressures and expectations to be a “good wife.” Expressions of a woman’s sexuality are considered shameful; the topic of virginity is both secretive and intruded upon by society. Dalia points to a portion of red calligraphy that describes the mould of a “perfect woman” — quiet, pious, innocent, studious, well-dressed in hijab, unconcerned with men.

“Honestly, I can relate to this stuff because I have heard women talking about this stuff in the previous generation. It was really terrifying for me, that they have accepted their own fate. It’s the way it was back then,” Dalia said. “The paradox in this for me is that they want the girl to be quiet, not care about boys, study a lot, and just think about that girl — if she is like that, then how can you expect her, once she is married, to do anything that her husband asks her? That’s not going to work. She’s definitely killing a part of herself to be able to live like that.”

Another section of red calligraphy urges women to not laugh “too loud” in public.

“We heard this at school a thousand times — don’t laugh too loud, it’s bad, it’s frowned upon. Good girls don’t laugh a lot.”

Dalia believes that Zahra’s story, written publicly on the walls, is freeing. It is witnessed on Zahra’s terms, her writing an outlet that she wields with piercing agency.

“I kind of feel like it’s freeing. Sometimes you build up all this shame and resentment in yourself for so long and it becomes a part of your identity, it becomes your weakness somehow, but I think if you have an outlet to just express yourself this way you can get free from it. Describe it on your own terms rather than someone else assuming things about you,” she said. “Very brave of her, I would say. Honestly, I would prefer to read it alone. I am pretty sure there are parts that will make me cry.”

Gender-based discrimination in Iran persists in the legal system. Dalia notes that her parents’ generation has tried to lift the mindsets underlying the oppressive dynamics Zahra documented.

“I think the next generation has tried to solve it, and actually our parents have changed a lot if you think about how they were taught and how they raised us.”

Ebrahim describes the audio in Grounding. He picks out mostly men’s voices “in the background” that hurl degrading judgments and conclusions about Zahra. He hears echoes of a “female sound reflecting rape stories and insults relevant to rape”. He hears a woman whisper “If I was a boy this wouldn’t have happened.”

“There is a part when everyone is screaming, that is the sound of a marriage, a celebration, a kind of forced marriage,” said Ebrahim. “The background is what is actually in her background, but the female echoes are what she thinks when she’s in the situation.”

He resonates with Zahra’s descriptions of hiding parts of her past in order to make space for herself in Iranian society.

“It just resonates a lot with me. This whole concept of ‘don’t do it, don’t show it, be careful’ — that applies also to the LGBTQ+ people in Iran. I think it’s very brave of someone to put this out and disturb other people who have to read it to get a sense of what they will never feel at all,” said Ebrahim. “My only thought is that there really needs to be a trigger warning.”

Ebrahim speaks to the necessity of exhibits like Grounding. They cause “disturbances” that awaken audiences to sociopolitical realities in the past and present.

“I absolutely think this is essential for people to remember why #WomanLifeFreedom matters and should not be forgotten. This kind of disturbance is essential,” he said. He reflects on the recurrent self-blame in Zahra’s story, her incessant ruminations on how others would shun her if they knew about her rape, and the numerous ways men hurt her. “All of this is not her fault. This is a general story that so many people experience in so many different cultures, but specifically Iran, and it’s a good reminder for people who don’t.”

He gestures to a scroll, thinking of the current protests in Iran.

“I’m happy to read it, especially this part. It’s her experience of a prison, and what might happen in future for our people.”♦

Gita Hashemi, Ebrahim, Salma, and Dalia reviewed content in this article prior to publication to ensure safe and respectful coverage. All student names are pseudonyms for their safety.

This article was published in The Antler River Media Co-op on January 19th, 2026:

A version of this article was republished in the February 2026 print edition of The Socialist:

https://www.socialist.ca/sites/default/files/sw_680_final.pdf