“Ongoing return”: A living archive of Palestine

Published in Antler River Media Co-op

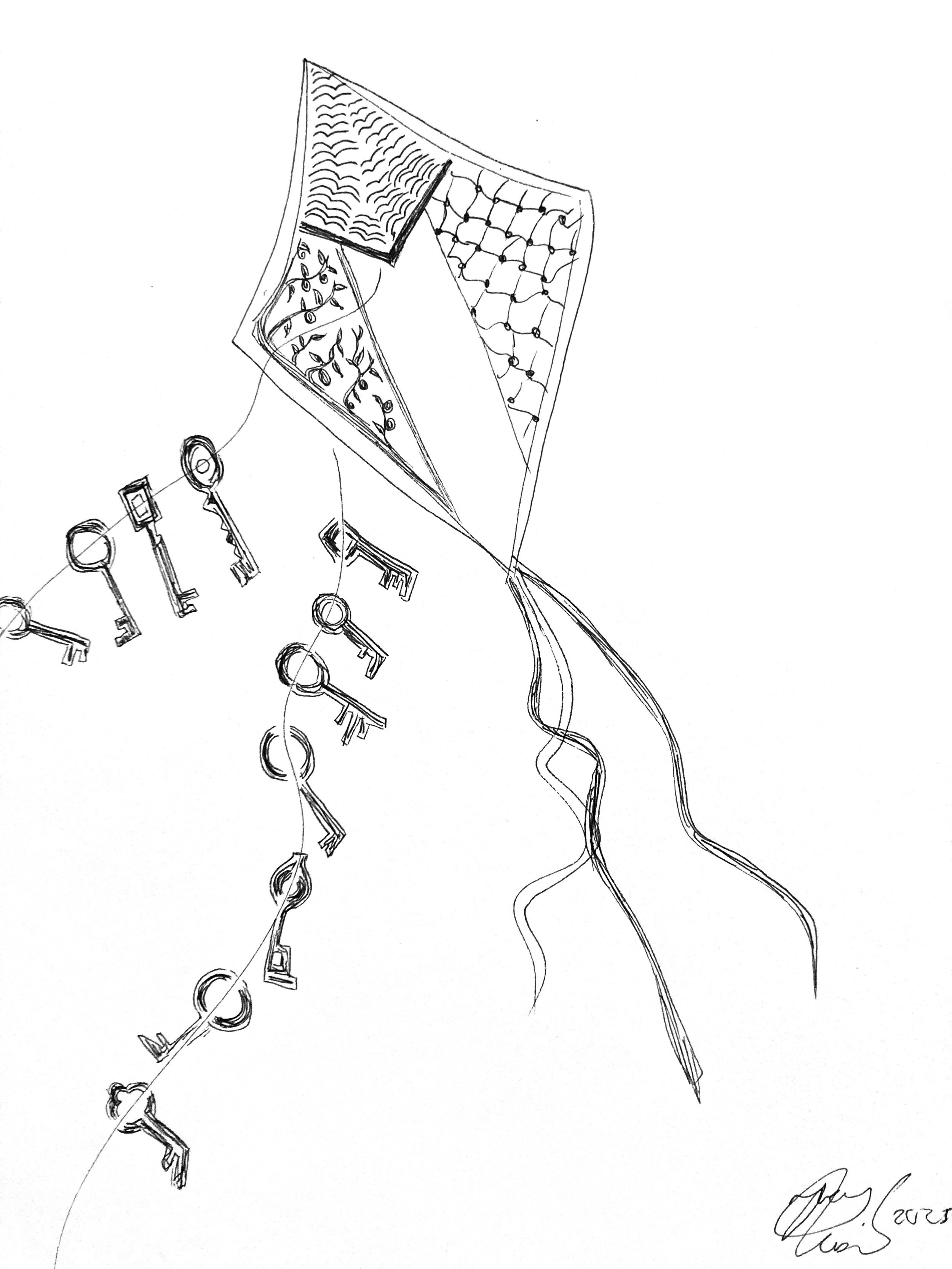

(*artwork by Incé Husain)

To cast my net I found the waves

Some laughing, some crying

The wave asked me ‘what's the matter?’

I said ‘I've lost my beloved’

Truly, I've lost my beloved

Partition, a film directed by McGill anthropology professor Diana Allan, begins with an Arabic song confessing to the sea. The lyrics ring against granulated black and white footage of the sloping hills and winding roads of Gaza, 1917. The scenes shift to British soldiers marching in synchrony and to explosions - grainy, soundless, and distorted.

Sleep, my son, sleep

The slumber of gazelles in the wilderness

Oh Lord, may my son grow

That he may come and go before my eyes

Watch over my beloved

And cradle him all night.

The silent footage is from the British Colonial Archives of Mandate Palestine. It was shot from 1917 to 1948 by the British during their occupation of Palestine, and is currently stored in an imperial collection in London, England. The Arabic soundtrack is from the Nakba Archive, a project co-founded by Allan that records stories of home and exile by Palestinian refugees in Lebanon; in Partition, Palestinians across Lebanese refugee camps comment directly on the colonial footage.

The marriage of these archives in Partition interlocks the past and present. It gives a new temporal state that “uses the present as a portal to the past and vice versa”. The titular “partition” refers both to the 1947 United Nations partition plan for Palestine and a “partition of senses” between image and sound.

“I use sound to reanimate and recontextualize these colonial images, interrogating archival authority, relocating these archives in the present, and restoring to song its political power,” says Allan. “This move to sound-silent footage with the reverberations of Palestinian life as it is remembered, lived, and anticipated, is an attempt to reconnect people, places, and temporality through the senses… The film is about this experiential aspect of archive, what it means to encounter one’s own past, and how the significance of that encounter might speak back to the present…You feel the weight of history in people’s voices in how they speak, the deep suffering that people have gone through.”

How vexing colonialism was, says a piece of Partition’s soundtrack, and how hard it was on the people of Palestine. We thought we’d be back in two weeks. It’s been more than 70 years. People still dream to return. The people become scattered across countries. And if this wasn’t enough, they dispersed families across nations.

Partition shows Palestinian schoolchildren writing on slates, their teacher pointing at a chalkboard filled with Arabic words. Women with draping head coverings sifting through trees. An almond grove in Jalil Al-Qibliyya, 1917; a mosque and well in Al-Majdal, 1917. Wedding celebrations and cattle markets in the Al-Khalil district, 1946. A Palestinian man smiling, eyes closed against the sun; I don’t know what he’s saying, but he seems happy or shy, the soundtrack offers. A village with arches, dispersed trees, a chain of mountains in the distance; if I were to enter this place I would certainly walk among the houses, all the windows are vertical as if the houses are looking at you. A young girl with large eyes sways uncertainly; she’s so transfixed by the camera, and then she walks, she’s so beautiful, I’ll call her Mirun, after the village my grandfather was displaced from. Large birds leaving their nests with outstretched wings.

I know you cry easily

Don’t cry, it will wound me

If my leaving hurts you,

Forgive me

***

“Witnessing genocide unfold in Palestine and Lebanon over the past 18 months has produced extreme cognitive dissonance,” says Allan in a talk for Western University’s Darnell Distinguished Lecture in Theory, Ethnography, and Activism on April 9th. “‘The scale and intensity of the violence collapses analytical distance. This intensive visualization of Palestinian death raises critical questions about the role of witnessing, and the power - our power - to see. With whose blood are my eyes crafted? [Feminist scholar] Donna Haraway asks, a question that we should also ask ourselves as we contemplate Gaza’s obliteration day after day.”

It is day 567 of Western-backed genocide in Gaza by Israel. Al Jazeera reported on April 12th that 50,933 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli forces and 116,045 have been wounded.

Allan thinks of Palestinian journalist Ahmed Mansour, father of two, who was burned alive in an Israeli strike on a tent full of journalists in Khan Younis the week before her talk. She thinks of her friend’s brother, who was shot in the head by an Israeli sniper while in line for food; two thirds of his family, residing in Jabalia, have been killed.

“Rage is empowering but also incapacitating,” says Allan. “‘Like many working in this field, I have wondered how to write.”

In February 2025, Israel dropped leaflets over Gaza. They read:

The world map will not change if all the people of Gaza cease to exist. No one will feel for you and no one will ask about you. You have been left alone to face your inevitable fate. There is little time left, the game is over. Whoever wishes to save themselves before it is too late, we are here remaining, until the end of time.

The livestreamed genocide mirrors the 1948 mass expulsion of Palestinians by armed European Jewish settlers that established the state of Israel. This mass expulsion - called the Nakba, or “catastrophe” - displaced and dispossessed 750,000 Palestinians, about 85% of the population. About 110,000 Palestinians fled to Lebanon, mostly from the Palestinian cities of Haifa, Akka, and Jaffa. Today, Israeli forces have displaced nearly 2 million Palestinians in the Gaza Strip according to a UNRWA report from March 2025, tripling the scale of the Nakba. Palestinian legal scholar Rabea Eghbariah recently proposed “Nakba” as a distinct legal concept akin to apartheid and genocide, with “displacement as its foundational violence and fragmentation as its structure”.

Israeli forces extended their victimization of Palestinians to Lebanon, bombing the Palestinian refugee camps of Beddawi, Ein el-Hilweh, and el-Buss in 2024. Twelve UN Palestinian refugee camps were erected in Lebanon after the Nakba; today, they house five generations of Palestinians.

“Gazan families pulling overloaded carts from north to south, from Deir al Balah to Khan Younis, mothers carrying children, ad hoc structures sheltering extended families, and countless other scenes of mass misery eerily recall the narratives I recorded for the Nakba Archive 20 years ago with Palestinians in Lebanon about their expulsion in 1948 when the state of Israel was established,” says Allan.

***

For over two decades, Allan has been documenting experiences of Palestinian displacement. She works with Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, organizing arts-based projects within the refugee camps that centre Palestinians as the creators, rather than the subjects, of archival work. This process of continuous documentation has created a “living archive” - ever-evolving, unfinished, and steered by those it reflects.

Allan shares that the living archive, an “undertheorized” concept tracing back to the 1970s, was defined by Jamaican-British sociologist Stuart Hall as “a self-conscious process of collective becoming, through which diverse materials might evolve into an object of reflection and debate…not an inert museum of dead works.”

“For something to be living and evolving, it must in some sense also be dying,” says Allan. “This runs counter to dominant Western conceptualizations of archives as static repositories of knowledge, locked in amber, forever bound to status formations of power.”

The living archive contrasts with the so-called “salvage model” that has driven most archival documentation of Palestine. Allan explains that the salvage model implies a way of life that is on the brink of death, a means to “find and restore cultural holes to ward off oblivion”, like that imposed by Israel consistently looting and destroying Palestinian archives and cultural heritage. The central archives in Gaza City, housing over 150 years of records, were destroyed; the Great Omari Mosque and its collections of rare books were destroyed; the libraries of all eleven universities in Gaza were destroyed; Gazans have been forced to burn books for fuel and warmth, with Palestinian professor Dr. Fayez Abu Shamaleh heartbreakingly feeding to the fire “one of our finest and most beautiful pieces of Arab poetry” by Iraqi poet Nazik Al-Malaika.

The living archive does not deny these losses. It places them within daily Palestinian existence instead of isolating them as relics.

“The living archive builds its forms in synchrony with existing forms in the life of the camp, which is fundamentally different from the salvage paradigm. It adopts the model of preservation, diffusion, and circulation through imaginative engagement rather than consolidation and conservation,” says Allan. “These histoires are carried in bodies and they are transmitted through bodies, and that will continue to happen.”

In 2002, Allan co-founded the Nakba Archive project with Palestinian activist and educator Mahmoud Zeidan. Over the span of five years, Allan and colleagues filmed 1,100 hours of interviews with first generation Palestinian refugees in Lebanon from across 150 villages and towns in Palestine. Voices gentle, rasping, and urgent, eyes impassioned, Palestinian elders shared memories of their lives before 1948 and of forced expulsion by European Jewish settlers.

“These narratives were a way to reassert the right of refugees to return to homes and lands from which they had been expelled and to hold accountable the forces that had produced their exilic condition,” says Allan. “The sense of urgency arose from a dual imperative - to transmit an ever-expanding traumatic past, and to take hold of an uncertain present and future for refugees languishing in camps across Lebanon.”

Ibrahim Mahmoud Blaybil, born in 1920 in Taytabah, Palestine, recounts memories of agriculture and primary school. Blaybil’s father was a farmer; the people of Taytabah cultivated wheat, watermelons, tomatoes, beans, zucchinis, and okra. He went to school in a small mosque surrounded by a garden, where he learned mathematics, Arabic, religious studies, art, and other subjects from an imam sent by the British Mandate. The British Mandate eventually constructed a school with limited classrooms. Blaybil moved to Safad to continue school.

If you were older than 14, they would dismiss you from your school. In order to keep people ignorant! said Blaybil. And, at that time, the British Mandate would pressure the fellahin [peasant farmers]. For example, during our growing season, they would bring in wheat, corn and lentil crops from abroad to compete against local Palestinian markets inside Palestine. Until people started hating the actions of the English. This led to the uprisings during the revolution of 1929. I remember it, there were planes flying over our town.

Blaybil went to al-Bassa to continue secondary school and pursue university studies. He became a strict, rigorous teacher, and taught Arabic, English, mathematics, and other subjects between 1943 and 1946 to grades one through four.

There were maybe two or three rooms. I was the one teaching them. While I was teaching handwriting over here, the best students were making others recite their lessons over there. I was dispatching the best students and sending them to the classes to teach other students, and I was overseeing them. I would write a maths problem on the blackboard in one room, and a maths problem on another blackboard in another room, and see who was able to solve it. And that is how I was simultaneously teaching all these subjects to three or four classes.

As a teenager, Blaybil recalls the British army coming to Taytabah when he was on his way to school with a friend. The soldiers harassed them and took them back to the village in a convoy car. The British had been trying to force villagers to build military roads for their army; Taytabah refused. As the car arrived, Blaybil saw the soldiers shoot his cousin.

Before we arrived at the village in the convoy, my cousin Yusif Abu Muhammad, God rest his soul, was farming. They ran after him: ‘Come here! Come here!’ He was farming with his two bulls. They wanted him to come to them, but he had to release the bulls because they were attached to the plough. They started shooting at him, and one of them hit him with his rifle and the blood started pouring.

As Blaybil shared his memories, birds sang in the Ayn al-Hilweh Camp where the interview was recorded. Behind him, a bouquet of yellow roses were spread in a vase.

Maryam Mahmud Sabha, born in 1920 in al-Zib, Palestine, recounts the British army’s violence in 1936 as they established checkpoints. She recounts events of the late 1940s, when colonizers forced twenty of her husband’s relatives to traverse landmines until they exploded. Ten were killed and ten were wounded; they were between the ages of twenty-two and around thirty. They had all worked in orchards.

[The British] would go up to the mountains, outside the village, and they would put up their checkpoints. And they would kill whoever crossed them, and whoever escaped, escaped. They made checkpoints for those who came from Tel Aviv, and those who came from the port and wherever else they came from, they would put up checkpoints and kill them left and right, said Sabha. They put [my husband’s family] in that truck and they made them go twice or three times over the mine they planted for them, but it didn’t blow up. On the last trip, it exploded and it killed a lot of people… They put in about 20 of them. Ten of them died and ten wounded remained. Those that were over there, in front … The big truck swayed forward, and those who were in the back, they all died. Ten died.

Husayn Mustafa Taha, born in 1921 in Miar, Palestine, witnessed the razing of his village by British-backed Jewish settlers. He fled with his family to other Palestinian villages, again faced expulsion by Jewish settlers, and finally settled in Lebanon. His uncle had helped build armed troops of about forty fighters to defend their villages, but the settlers - armed by the British - had stronger ammunition.

They took us to the outskirts of the village in order to blow it up. They did not keep us inside the village. They gathered us and they took us outside the village at a distance of five kilometres. No, not even five kilometres. Two or three kilometres away from the village, and then they exploded it. [We] began rebuilding it and started working for the revolution, joining the revolution, attacking the Jews, attacking the British…[The Jews] came from the west of Miʿar, and they started shooting at us and we were shooting at them. They defeated us with their ammunition; they reached Miʿar and they kicked us out, said Taha. I left with my children. I took my children and my siblings. My son Muhammad, and Fatma – they were young. They were two or three years old, and I got them out. My father and my mother stayed there, in Palestine. The elders stayed in the village. But the young men, they kicked them out, they told them: ‘You’re not staying. Either you go, or we massacre you all.’

Taha has a keffiyeh wrapped around his head. He says he would have shared more of his past if he wasn’t ill, and that he still hopes to return to Palestine. About halfway through the footage, the voices of children are heard in the Miye wa Miye camp where the interview was recorded.

For Allan, the interviews’ inclusion of sounds from the camp deepens understandings of the narratives. They provide a glimpse of the social and material contexts in which refugees form their recollections, tying memory to place. In this way, Allan considers the camp itself to be a living archive.

“It would be meaningless to collect oral histories as if they could be abstracted from this context. These narratives arise from these spaces and draw their vigor and meaning from them. I am thinking of [the camp] as a political material form, not only for understanding histories of colonialism, humanitarianism, state-making, forced displacement, but also refugee life housed and held for almost eight decades, where people create intimate social material worlds of great epistemic importance,” says Allan. “They are sites of resistance where refugees continue to challenge paradigms of apolitical objection. They offer a vision of Palestine and what it means to be Palestinian. In its very material endurance, it keeps the moment of dispossession unresolved. When camps are destroyed, refugees rebuild and reassert these claims. As sites of communal knowledge, historical memory, ongoing return, they continue to pose a threat to the Israeli colonialist psyche.”

In the Foreword of Allan’s book, Voices of the Nakba: A Living History of Palestine, her colleague Mahmoud Zeidan writes of how camp life fuses past, present, and future:

I never read about these events – or even our village itself – in history books. I don’t know how I came to know what I know about it. I know the stories of Safsaf as I know the houses of ʿAyn al-Hilweh, its alleys and its people. Like many others in the camp, I know these stories as if by instinct. They blend with our present everyday lives to the extent that we don’t regard them as belonging to past time or history. They present themselves naturally, without effort and in any occasion. They don’t result from a question or seek permission. These stories thrummed the tents of the camp and flew like the driving rain. They hung in the air in later years, among tin houses, spreading like the scent of food and attracting neighbours, relatives and passers-by. They echoed through time from tin houses to serried concrete flats, passing through winding alleyways from home to home during the very many occasions that gathered together parents, neighbours, relatives and loved ones.

The interviews with Palestinian elders - one of the largest audiovisual collections of refugee oral histories from pre-1948 Palestine - are primary sources for historians and activists. In 2010, they were donated to the Palestinian Oral History Archive at the American University of Beirut, where they were re-digitized and indexed. In 2019, the archive became virtual and open access, reaching people across the world. But the camp communities themselves could not access the online realm, with many refugees lacking digital devices. This barring created a “paradox”: the Nakba Archive became available to global audiences and separated from the communities whose histories it holds. Allan turned away from preserving the archives through institutions and instead sought to return them to the camp. She hoped to “enliven, circulate, and reactivate” the interviews through collaborative arts-based projects within the camps. These projects might spawn new works that feed from the interviews and respond to current conditions, fulfilling the self-evolving nature of the living archive.

“The term ‘living archives’ often appeals to an emancipatory digital democratization, but where does this leave refugee communities who cannot access the digital? Who ultimately are these histories being preserved for? Who archives and who gets archived, and who ultimately benefits from such projects?” says Allan. “If the place of the archive itself were to be democratized, redistributed, moved out of the purely digital domain and brought back into the camp, what new life might it have?”

***

One form of new life enacted by the return of the archive was the soundtrack for Partition.

Another, in 2022, was a short story writing session held in the Al-Jalil refugee camp in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley. Eight emerging Palestinian writers were invited to listen to the Nakba Archive interviews and talk with elderly Palestinians. The stories that emerged - conveying camp life with humor, wit, and irony - are pensive conversations between the Palestinian writers and elders. Allan describes them as “tracing lines of continuity and intergenerational differences, taking the form of a meta-commentary on the act of remembrance itself.”

One writer, Sarah Daoud, titled their piece “Queues”. It commemorates a realization that “queues have become a part of the Palestinian’s memory, a part of his past and his present, a part of his existence.” Daoud writes:

Ration queues, fuel queues, food and drink queues, stationery queues, blanket queues, clothes queues, the queues of the first Nakba, the queues of displacement from homes, the queues of bodies, the queues of the wounded, and many other queues. Queues queues queues chasing after us. So many sights of queues fill my mind, queues I have seen, queues I have experienced, and others I have witnessed on television, queues I have heard about, queues my grandmother lived to tell me about. Sights and sounds of queues blending together all jumbled in my mind, until I got lost among them, which ones did I see with my own eyes, and which ones were a figment of my imagination that I experienced because our grandmothers told us about them, so much that they became real stories in my mind. I remember one of these queues, it was a part of my childhood in al-Jalil camp, it was the queue for the rations distributed by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) to the Palestinian refugees in our camp. In these moments, I remember the distribution days and I feel a fleeting smile, etching itself on the edges of my lips, I know it all too well, this mocking smile… I smile wondering, this cause for pain today, how could it have been the reason for joy back then?! Usually, it’s the contrary, what hurt us in the past fades over time and becomes the opposite. But in this case, what pains me today is what used to bring me joy in my childhood. I can see myself, carrying a backpack that could break the back of a camel, how did it not break my own back! Inside it are books and notebooks that weigh half of my weight, and I’m ten years old, coming back home to the camp from the UNRWA school. If I take the “upper” road, I can get to my house in just two minutes. But a curious and adventurous girl like me would not miss the chance to go watch the distributions and the ration queue, even if it meant carrying her bag longer and further, so I take the “lower” road.

Another writer, Oula Jomaa, pondered the feelings of Abu Adel, the Palestinian man who first opened the iron gates of the Al-Jalil camp in 1949 and led others inside. Adel’s sister tells this story with pride. In “Abu Adel, the opener”, Oula writes:

I wonder and ask myself: what is the psychological state behind this story? What is the true feeling? What exactly is her pride and admiration for this great opening? I think about Abu Adel, the opener, opener of the refugee camp, opener of refugees' lives... And I wonder, how did he feel at that time? And how is he now? I wonder, did Abu Adel know, when he opened the gate to the camp, that he was opening a prison for us and them, and that this prison’s verdict is still postponed until now? And we don't know until when… I had always wondered how someone who lived through the Nakba and lost what they lost during it, could keep living after the Nakba, and have a new life, a different life, a life with its share of happiness and sorrow. I think I have the answer now, I think I found it thanks to Rajab al-Masri, thanks to Abu Adel the opener. It’s the survival instinct, and we Palestinians have mastered it to the extent that it is no longer just an instinct, it has become a goal, an end, and a necessity. In reality, we’re not given the choice to either continue life or stand still. To live and build a new life for yourself is not an option or a negotiable decision. It is an imposition, a duty, a solution, and your only way to go, and no one will excel in it as you do. As a Palestinian, you must abandon your human weakness and helplessness, your sensitive feelings, or at least hide them and ignore their existence. You must understand that they hinder your ability to survive, for you were born to remain. You were born because you have a land that was stolen from you, and it is your duty to reclaim it. You were born because you have rights that have been violated, and it is your right to reclaim them. You were born to live, to remain, to renew the generations, to return, and to live.

***

Some documentation work on Palestine also seeks to shield camp life from a global gaze, and instead convey camp histories through "listening and taste". This serves to challenge the presumption that “every aspect of Palestinian life should always be available for viewing”. Lammeh, a Palestinian art collective based in and around Tyre, collaborated with artist and photographer yasmine eid-sabbagh, who created and curated a large collection of photographs in the Burj al-Shalami refugee camp near Tyre. Together, they sought to “expand the concept of what a photographic archive can be by translating images into other sensory registers.” Allan collaborated with them by organizing a sound recording workshop in Beirut in August 2024 which aimed to “explore sound as a medium of expression at a time when images of genocidal violence have come to dominate our perception of Palestinian life.” She shared an excerpt of a sound recording, composed by Bahaa al-Jomma, that features nai, a type of reed flute. The notes are soft, hazy, lilting, and nostalgic to another time.

“The aim has been to expose the person listening to all the disembodied and affective layers of the photographs,” says Allan of Lammeh and eid-sabbagh’s work. “These sound workshops that I’ve been working on have been an opportunity to think collectively about how music - but also how song and ambient sound recordings - mediate Palestinian presence through acoustic images.”

Allan shares that many Palestinian artists, writers, and scholars - such as scholar Abdaljawad Omar, professor of Middle Eastern and North African Studies Nasser Abourahme, writer Adania Shibli, and poet Mohammed El-Kurd - believe that bearing witness to the atrocities committed by Israeli forces against Palestinians no longer accomplishes anything.

“They argue that Western-facing conversations and performances of victimhood have only deepened Palestinian dehumanization,” Allan explains. “There is a weariness of telling the same stories over and over again to foreign researchers, journalists, people who come with this assumption that this appeal - that is always directed to an imagined audience to the West - will somehow bring dividends when people know now that it just won’t.”

Similarly, Allan explains that Palestinians may refuse to share stories. It allows them to defy “settler time” and build their own sense of truth and future. These truths include convictions of hope that may seem “outlandish to distant observers.”

Allan shares, for example, that the Gaza genocide has emboldened Palestinians in Lebanon, with one saying “despite our loss, we have gained a lot, I see it as a victory.” Palestinian historian Rana Barakat believes that “documenting what has been done to us has bound Palestinian memory and history to settler colonial time and power,” fixing Palestinians in “projects of museumification” that imply Zionism’s success. Palestinian anthropologist Reema Hamami echoes Barakat, suggesting that the term “ongoing Nakba” might be replaced with “ongoing return” to emphasize Palestinian steadfastness.

“This call to think beyond the paradigm of loss and absence may seem paradoxical, even audacious, in the time of genocidal erasure, and yet this sentiment is shared by many Palestinians in the communities in which I worked and have long shaped my conversations,” says Allan.

Last fall, Allan wrote a short essay that included these concepts of resistance. The editors asked her to remove them, claiming they were insensitive to the grief of Gazans.

“I have since wondered if their reluctance might reveal an inability or unwillingness to recognize the structures of hope that do exist, or perhaps even and especially, in the face of insurmountable loss. And it may also stem from the liberal pieties about the illegitimacy of Palestinian anti-colonial armed resistance and what kinds of actions can be seen as hope,” Allan says. “As Westerners - with different understandings of risk and loss - we are habituated to see, in the Palestinian lot, defeat and devastation, where the Palestinians themselves, through long experience, have learned to insist on possibility, continuity, and return that, being iterative instead of prophetic, always begins now.” ♦

NOTE: on April 28th, 2025, two changes were made to this article following correspondence with Dr. Diana Allan. One involved a rephrasing of a term, and the other clarified details in one paragraph.

This article appeared in The Antler River Media Co-op on May 7th, 2025:

https://antlerrivermedia.ca/ongoing-return-a-living-archive-of-palestine/