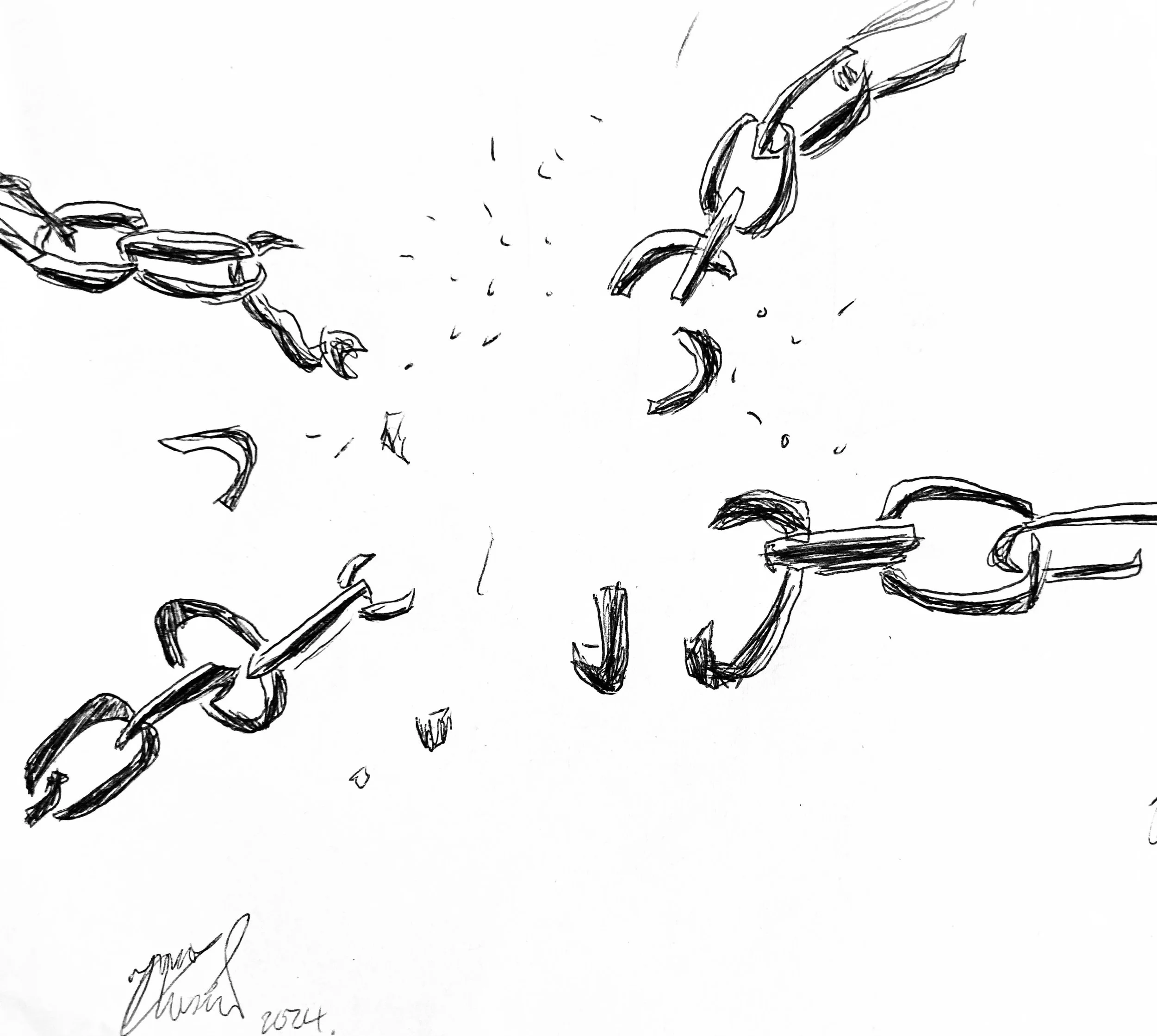

“The loosening of shackles”: Understanding Emancipation Day

Published in the NB Media Co-op

(*artwork: 'The loosening of shackles' by Incé Husain)

August 1 marks Emancipation Day, a commemoration of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. Actualized on August 1st, 1834, the act freed slaves across the British Empire. Emancipation Day was officialized by the Canadian government in 2021 as a time for Canadians “to reflect, educate and engage in the ongoing fight against both anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism and discrimination... Emancipation Day celebrates the strength and perseverance of Black communities in Canada.”

This year, a room in UNB’s library was rich with a panel discussion about the meaning of Emancipation Day. The panelists were Nadia Richards and Yusuf Shire, UNB VP Human Rights and Equity, and President of the New Brunswick African Association, respectively. Dialogue was guided by Joanne Owuor, UNB Human Rights, Equity Advocacy and Education Officer.

The panelists shared their personal interpretations of Emancipation Day, how Black history should be taught in Canadian education systems, how journalists should report on stories about Black communities, and distinguished emancipation, liberation, and resistance. The event was organized by UNB’s Human Rights Office.

The panelists described Emancipation Day as a time of celebration, reflection, and the “loosening of shackles”. They experience the day with “some form of freedom” that coexists with a “consciousness of oppression”. The nature of these feelings differs across Black communities, like those in Africa and the Caribbean. They believe that these experiences may be united by sharing histories and stories, giving rise to a commemoration that is “inclusive, but keeps these entities”.

The panelists shared that, historically, emancipation referred to individuals who were freed from slavery, and that this freedom was based “not on hearts but economics”: emancipation was a mere strategic tool to shift the British Empire’s economy while maintaining its control. Liberation, therefore, is fundamentally different from emancipation. It is taken, not given. It is to fight “psychological enslavement”. It is to legally dismantle systemic oppression.

“Emancipation was given to us by the British, so it was not true liberation,” says Shire. “Liberation is an individualistic framework: we’re fighting systems of oppression, not literal slavery. Black emancipation has happened but Black liberation is still continuing.”

The panelists distinguish “liberation” and “resistance” in terms of those who take part in human rights movements. People who are of the identities under direct threat are always fighting for liberation: they cannot escape their body and its political consequences. People of other identities can both nurture and shed their connection to the movement; they have the privilege of resistance.

Richards says this distinction gives rise to two roles in human rights movements: the ambassadors, and the protectors. The ambassadors are those who are fighting for their liberation. The protectors are those who resist and keep the ambassadors safe - practically, emotionally, within and outside the movement.

Richards says these roles broaden the scope of activism. While ambassadors embody raw experiences that can catalyze action, protectors can advocate in contexts where ambassadors may be threatened, dismissed, or overwhelmed. Such situations could include dialogues with politicians or administrators who maintain oppressive systems.

“In movements, you have two kinds of people: those who are impacted, and those who are doing it to look good,” says Richards. “Within the first, if you are (of the identity the movement is about), there is no question that it is for your liberation. If you are not, and you are impacted, then you can step outside of that. That is the difference between liberation and resistance.”

Shire and Richards believe that the legacy of liberation efforts must be “unleashed”. Discussions on oppression, anti-Black racism, anti-Palestinian racism, Islamophobia, and Indigenous rights must course through town hall meetings. Stories must be shared and meaningfully heard to begin changing political systems. School curriculums must be infused with Black history. Young people must be equipped with self-awareness and vigilance.

For Shire, the “biggest enemy” of the Western world is technology. He references how social media is currently erupting with footage of the genocide in Gaza, awakening the world irrevocably to Palestinian history.

“Education is Europeanized, but technology has forced information to the surface,” he says.

The panelists list some key figures from Black history that all should know: Queen Amina, Shaka Zulu, and Jean-Jaques Dessalines. An audience member mentions Patrice Lumumba.

Queen Amina was a warrior queen who ruled in pre-colonial Nigeria in the 16th century. She was the daughter of the King of Zazzau (present-day Zaria in Nigeria), fought as a warrior in the army for a decade, became queen after her brother’s death, and expanded Zazzau territory to its largest in history through a series of conquests. She built protective walls around the area she conquered; many still stand today and are known as “Amina’s walls”. (See subheading “Charisma, Sexuality, and Governance: A Case of Queen Amina of Zaria and Catherine the Great of Russia”)

Shaka Zulu ruled pre-colonial Southern Africa in the 18th century as king of Zulu. He united militaries across Southern Africa, integrating conquered tribes into his army and allowing them self-governing, loyal chiefdoms. By allying over a hundred chiefdoms fortified by a shared army, Zulu’s rule nurtured common identity, diversity, and pride across Southern Africa.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines was the first Emperor of Haiti. He was born a slave in the 18th century French colony of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) and led a revolution under Toussaint L’Overture, also born a slave, that liberated the land from French colonial rule. Dessalines renamed the land “Haiti” – for a word meaning “land of the mountains” in the language of the Indigenous Taíno people – and became its emperor in 1804.

Patrice Lumumba was the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He was a postal worker who gave speeches on the tides of anticolonial revolts, negotiated the Congo’s independence from Belgian colonial control, and took office in 1960. He was a natural leader - charismatic, brilliant, and self-educated. His presidency lasted only three months. Following Belgian attempts to regain control of the Congo, he was killed in a CIA-backed assassination. He was only thirty-five years old. His tooth - all that remained of his body and collected as a “trophy” by a Belgian policeman - was returned to his family for burial two years ago.

The panelists believe that knowledge of these figures counteracts a “whitewashed” history that “forces Africans to prove their contributions to humanity”.

Shire adds that everyone should ponder the fable-like stories about the world they were told as children. These narrations were likely embedded with cultural, historical, and global meaning that becomes clear later in life.

“When an elder dies, it is like a whole library has burned down,” says Shire. “Go back to your history. They used to tell us stories as children that now make sense.”

For example, he shares that African countries are known for having an abundance of gold and minerals: why, then, do they have the lowest currencies in the world? Haiti is projected to the world as being stifled and poor; in truth, Shire says Haiti is “paying the price” for achieving liberation from the French (see subheading “History”).

In the media, Richards says that responsible journalism must convey an awareness of “true Black experiences” - the physical, the psychological, and the emotional. These insights will nurture dialogue about how people of Black communities can protect each other.

She says the media must also document anti-Black discrimination with thoroughly gathered evidence. This will unburden Black communities from having to “fight with their own words” in ploys that harangue and dismiss their experiences.

“(Journalists should) focus on those who are harmed the most rather than educating the masses,” says Richards. “We cannot let the media tell us how to support our community. Be humble and try to do the work that our people need.”

Shire adds that the media can “make the most evil person a saint”.

“It’s time for action instead of talking,” says Shire. “When you know who you are fighting with, you know that you don’t have time.” ♦

Nadia Richards and Yusuf Shire were consulted about this article prior to its publication to ensure the Emancipation Day panel was respectfully covered.

This article appeared in The NB Media Co-op on September 11th, 2024:

https://nbmediacoop.org/2024/09/11/the-loosening-of-shackles-understanding-emancipation-day/