Before my scalp went cold and then caught fire

*NOTE: Why am I posting my journal entries? See my inaugural post: Beyond journalism

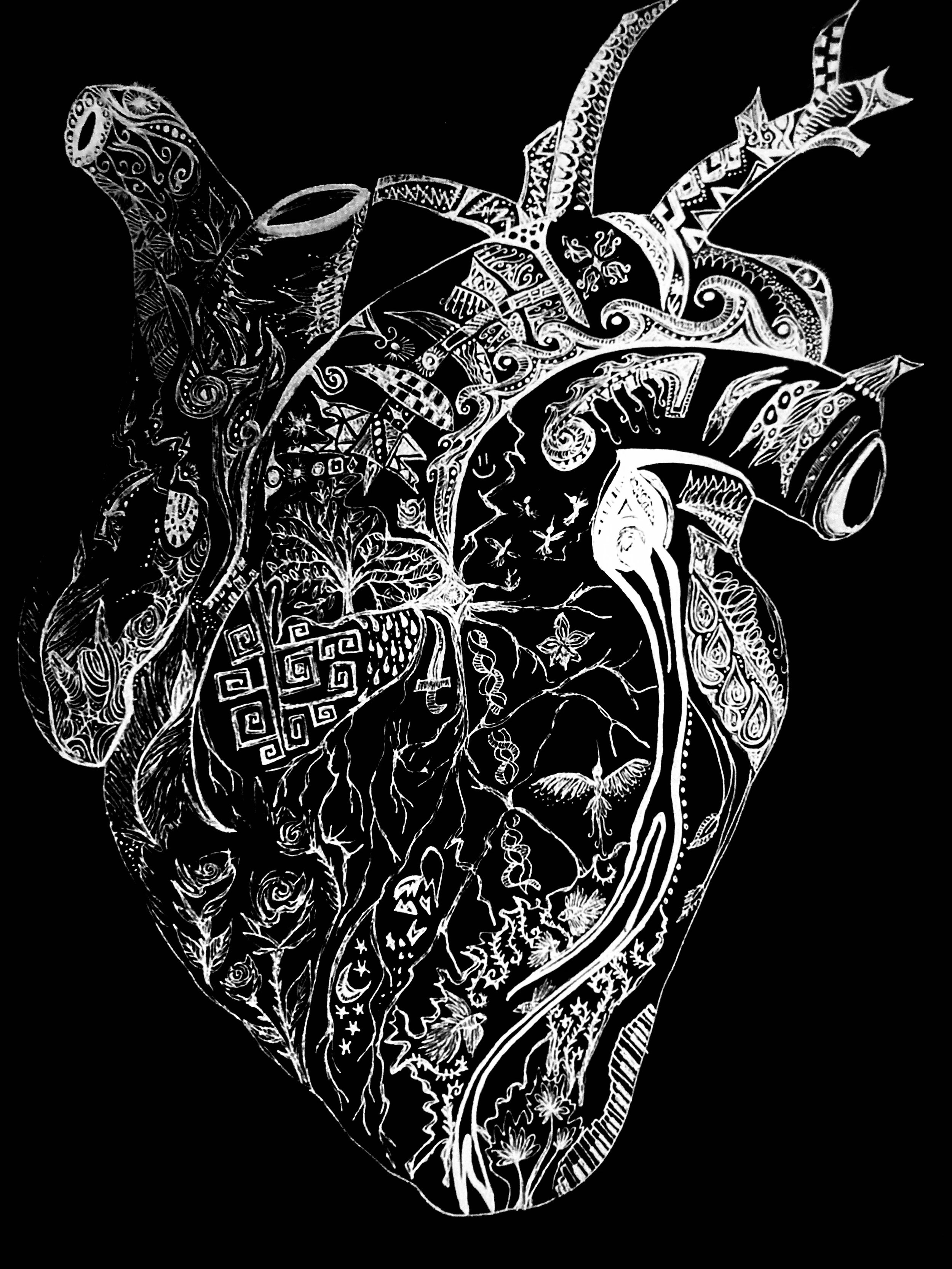

(*artwork by Incé Husain)

I wake up to news that Pakistan and India have agreed to a ceasefire. I wake up to news that the ceasefire has been broken. I wake up to news that no news on Pakistan and India is to be trusted. I cycle from Al Jazeera to BBC to Dawn to family group chats, a process of elimination: what is consistent, what is inconsistent, what is vague, what is uncontextualized, what is unverified? What is unlikely - based on my intergenerational Pakistani intuition? What does intuition imply for choosing what news to believe and what to discard, when the news is that a city my family lives in has been bombed, when the consequence is to open the floodgates of panic and prayer, the hijacking of my brain circuitry?

Three days ago an Al Jazeera headline said “Blasts heard in Pakistani city of Lahore”. When I read this, before my entire scalp went cold and then caught fire, a singular lucid thought reverberated in a state of calm: What a strange way to see Lahore written, identity-less except the reference of Pakistan and the coordinate of a blast. Like it isn’t its vibrant, green, red sun and smog pulsing self. Like the soul has been taken out of its eyes.

I FaceTimed X, started crying before the call connected. “Oh god,” he’d said. Y started cross-checking with other news: Al Jazeera said it is citing Reuters, Reuters said it is citing GeoTV, GeoTV has reported nothing. Z checked with family.

“I came from there - didn’t see anything,” said my mom’s cousin in Lahore. “Not sure how to rely on social media things!”

I hadn’t thought for a second that the news might not be true. Even as I said, on FaceTime, “I guess Al Jazeera got it wrong,” the words felt traitorous in my mouth. My scalp was still on fire, the rest of my body dead weight.

An Indian government official said “not a single drop” of water will enter Pakistan. India suspended the Indus River Water Treaty that underlies 80% of Pakistan’s water source that feeds 250 million people. Indian Prime Minister Modi said he would hunt the attackers “to the ends of the earth”. India said, without evidence, that Pakistan was responsible for a terror attack that killed 26 tourists in India-occupied Kashmir. Pakistan denied involvement, condemned the attack, demanded proof of Pakistani involvement, and said it would participate in “any neutral, transparent and credible investigation.” No such investigation has been done. I taste those words: Not a drop of water will enter Pakistan, hunt them till the ends of the earth. Their bluntness rings.

“They bombed actual cities in Pakistan,” Z said, when India struck villages and mosques in Bahawalpur, Muridke, and more, called them terrorist sites and killed 31 civilians. “These are not in the Kashmir region where the attacks happened. These are Pakistani cities.”

On Thursday morning, my cousin in Lahore said a drone was shot down over Lahore. I checked the news and there was nothing about Lahore. Z called me while I was brushing my teeth. She said that family in Lahore, Karachi, and Islamabad are hearing blasts and houses are shaking. I checked the news again; these cities were nowhere.

I thought of the family in Pakistan who I would see for just a few days a year, who would take me into their arms and feed me whatever I wanted and laugh with me and love me on principle, beneath the sun, in gardens, in sprawling glowing homes. I started sending messages to Pakistanis I know, asking if they’re okay. It was the silly question I mass-asked, in the past year, to people I knew with ties to Palestine and Lebanon: Are you okay, I hope you’re okay, that your family is okay, that your friends are okay, if there’s anything I can do, anything, tell me. But this time, I added an additional line. My family is safe for now, alhamdullilah, they’re in Lahore, Karachi, and Islamabad. The “important” cities, Z says, in war times. Lahore, close to the border. Karachi, the most populous city. Islamabad, the capital.

Yesterday, a Palestinian friend asked me if I was okay. He told me he is furious because he sees India enacting the Israeli recipe. He said the world didn’t stop Israel from starving and bombing Gaza, and this has taught world leaders that they may repeat its methods freely, try their hand at the norms of illegal warfare and its parading. Bomb cities, cut off water, say it loudly, what you’re doing, blame it on terrorism, prove nothing. Gloat about it. Mama said she saw a video of Indian nationals celebrating the killing of a Pakistani child.

When I checked the news on Thursday, the vast majority of headlines said that India had bombed Pakistani terrorist sites. I was jarred, scrolled further, trying to find sanity, a single headline that said no, they were not terrorist sites, they were mosques reduced to rubble and 31 civilians who were killed. The assumption of the headlines rings: there are no civilians in Pakistan.

India has blocked BBC, The Wire, international news accounts on X, Pakistani and Bangladeshi media channels on YouTube, and freelance journalists, a media void that will birth parallel universes of who bombed who and when and why. I tried to tell Q this, the information burial, the nausea rising in my chest, the sense of being buried myself in this erasure and warping of identity, how it would stuff a stranger’s gaze with alien rhetoric about my fear and cut out my tongue. Could I tell anyone who sees this news that my city is being bombed without activating in them a sense that I deserve it? Could I convince anyone that a mosque is a mosque? Is this why so many people I know who tune into the news, who know I’m Pakistani and have family there, haven’t asked me if I’m okay when I’m at my most shaken? There’s nothing like the word “terrorism” to hijack the West’s sense of who ought to be bombed. It’s their clickbait, their tribal drum, the word that trumps and blinds everything, and my life has told me clearly that “terrorist” has always branded the Pakistani more than the Indian. I feel checkmated before I begin, even though my people were killed for sport. But Q is Lebanese and doesn’t need this speech. She says: “Modi is friends with Netanyahu. That’s all anyone needs to know.”

I called Z repeatedly and said the same things: I don’t know what news to trust, I don’t know what’s happening, is it true that the Pakistani military struck temples and villages in India too, is it true that the West hates Pakistan because it sees a radical terrorist hub and so most press will lie? And if so, how do I give people things to read when they ask, without being met with the same criticism - that I am giving them what I want them to believe? Who am I to decide what is propaganda and what isn’t? What proof can I give that some press is lying and the press I read isn’t? It confuses my fear and my sense of urgency without minimizing its intensity. It leaves it blind, half-fed, half-rabid. My dread is uncertain, unfinished, fractured.

Intergenerational intuition charges again.

“You won’t need to convince anyone who’s Palestinian or Lebanese,” says Z. “The second they learn that we’re being bombed by Israeli missiles and hear India’s rhetoric, they’ll know whose side they’re on.”

“Why would Pakistan attack Indian cities and temples?” says Y of the news that Pakistan indiscriminately attacked the Indian city of Amritsar and occupied Kashmir. “Pakistan has a fraction of India’s army, is in dire economic crisis, Amritsar is in Punjab and has strong ties with Pakistan, and occupied Kashmir has majority Muslim populations. That would be very, very stupid. But I think Modi, who is fascist and hates Muslims, would bomb Muslim majority areas in India and blame Pakistan.”

“India-occupied Kashmir, the most densely militarized zone in the world, with 30 soldiers to each civilian… they couldn’t catch any of the terrorists after the attack? They escaped that easily into Pakistan?” says Z. “Does that make sense?”

“What does it mean when a government blocks news,” says Z. “Why would they do that, after violating UN treaties and openly saying they’ll cut off a country’s water supply?”

“They always try to gag the media when they know they're about to do war crimes,” says a Lebanese friend.

“They’re sowing the seeds of consent with fear mongering,” says another Palestinian friend.

“I’m sorry for what my country is doing to your country,” an Indian friend texts X.

None of these are facts. They clarify nothing. They are lenses of narrative that rake the contradictory statements presented as fact, lenses that will not be in the news, lenses that I call “intergenerational intuition”. They try to graze whatever truth forms the premise for why there’s propaganda. They try to serve the function of news: to convey the who, what, where, when, how, and why. The actual news is not serving this function. The actual news is a soup of contradictions that does not provide the tools for navigating it. The tools come from being part of the news itself. This is ironic, because the news is meant to convey the truth to those beyond. A Pakistani friend writes to me that he too feels the weight of the disinformation, that he too will tell me if he find any news that “feels right”.

So this is the state of reading the news: if it feels right, “if you know you know”, if you don’t then you’re at the mercy of the disinformation spears, and the holes they puncture will make your skin more ripe for the next wave. How to fight this? I don’t know.

The answer is not necessarily to build intergenerational intuition. This intuition is not a foolproof tool. It is not always a laser that slices away the blindfolds. It also carries the stain that comes from being the victim of disinformation, that also biases it into forms of denial.

My parents lived through the 1971 war between Pakistan and India, in which East Pakistan gained independence from West Pakistan to become Bangladesh. In Bangladesh, it’s called the “liberation war” or “war of independence”; the Pakistani military committed mass atrocities against Bangladeshi civilians in Operation Searchlight that sought to snuff out all Bangladeshi resolve. My uncle called it a genocide. “Of course the Pakistani military committed a genocide,” he’d said, not a single note of hesitation. There was an information blackout in Pakistan while it was happening.

“We had no idea what had happened until we left Pakistan,” Z had said. “If I told your grandfather, even now, he wouldn’t believe that the Pakistani military had committed those atrocities. He never believed it.”

“I was a kid. I was in Turkey in 1971, watching from afar,” Y had said. “We were getting the information about the Pakistani military. Your grandfather wouldn’t believe it. There was just this sense that the Pakistani military wouldn’t do that, couldn’t possibly. There was no question.”

Sometimes intergenerational intuition is not a tool that allows critical questioning. Sometimes it is just nationalism. Sometimes it is denial and shame. I try to tread carefully with it. I would certainly rather have this lens than none at all. In the absence of any such lens, the West will get their first and manufacture.

And then there is Kashmir, the “why” of all this, the illegal Indian occupation, the most densely militarized place in the world, the place of lush valleys and mountains. In 2018, when I was in Nathia, in the foothills of the Himalayas, I was at the dizzying foggy mountain peak that overlooked the Neelum Valley in Azad Kashmir. I have been reading constantly about Kashmir now. Sometimes I feel that my knowledge is so lacking, the questions I ask so elementary, my sense of something key to my Pakistani roots so fuzzy, that I forget it’s part of my history. I have the sense of forgetting that I’m Pakistani.

“Kashmir is in chaos”, says S from Kashmir, with her ties to both Azad Kashmir and India-occupied Kahsmir. Both regions are under bombardement. Muzaffarabad, the capital; Kotli, Jammu, Srinigar, others. Exchange of fire at the line of control between occupied Kashmir and Azad Kashmir, always somewhat present, is now heavily heightened. S sends me videos from family of what this looks like: red, unsprung fireworks. Video taken from a speeding car, someone says in the background “hurry, hurry”.

Some people in my circles who are paying attention to the news say that the exchange of fire between Pakistan and India is a distraction from the violence in Kashmir. I agree that if things escalate further between India and Pakistan, the focus on Kashmir’s 78-year-long occupation might fade from human rights groups and become replaced by imagery of broader war.

But to use “distraction” to describe any warfare between India and Pakistan implies that concern for my family’s safety - in Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad - is a distraction. It means the words “not a drop of water will enter Pakistan” is a distraction. It means “we’ll hunt the terrorists till the end of the earth”, when that earth is Pakistan, full of 250 million people, is a distraction. This rhetoric of dismissal, by including these statements by India and its killing of 31 civilians beneath the “terrorism” card, scares me. I know that Kashmir is more victimized, and that the manifestations of India’s Netanyahu-worthy statements have not fully come to fruition, but there has to be a better word than “distraction” for its beginnings.

Last night, I was so exhausted that I came home from work in the afternoon and slept for five hours. I nodded off even on the bus home, head lolling against the window. When I finally fell into bed, my dreams were in denial. They had me running from something, from campus and its contentment with the world order. But I soon locked shut like a clam. It was a blackout sleep, vanished me like jet lag. In the minutes when I’d sporadically wake, I could return to the blackout easily, thinking: Please shut me away, let not a shred of these past few days find me, let me find a sanctuary. And I did, subhanallah. And there was a flicker in my dreams of the encampments, which made me smile when I woke up in the sun. What a stark difference between what I am today and what I was this time last year, or what an alignment. Yesterday last year I chanted on the encampment lawn “Gaza, Gaza, don’t you cry”. Yesterday this year I said at the grad club “my city was bombed.” The people of these statements are targeted by the same Israeli missiles.

“My country’s being bombed, your country’s being bombed, my best friend’s country’s being bombed,” said Q. The tone in her voice: what the heck is happening to the world?

When I wander downstairs into the quiet kitchen, make chai and an egg, my family WhatsApp group is making jokes. They send Instagram reels of Pakistanis mocking Indian missiles. A cluster of Punjabis contemplate an orange fire from the Indian explosion, cackling that it conveniently killed all the mosquitos. One explosion site attracts passersby who gaze at the wreckage, so a man sets up a stall selling pakoras to enhance the viewing experience. Someone joked: you want Karachi? Take it! It’s a mess, you’ll give it back in a week. Someone else says: India hasn’t seen anything yet, they’ve only seen our missiles, they haven’t seen the damage that our mother’s chapals [slippers] can do. I talk with my cousin and re-immerse myself in the roots of the absurd, overblown Pakistani humor I grew up with. Now, it is contextualized. This is why we dance, this is why we laugh; I’ve seen this wit before, when I wrote about Palestine, about Lebanon, about Yemen. Now it’s my turn. I feel distinctly Pakistani, laughing till 3am.

My aunt sends an essay by Zara Shahjahan called “When the meme is mightier than the missile”. An excerpt reads:

“…the laughter is not a sign of naïveté—it is the weary chuckle of a people who have lived too long in the shadow of existential dread. For a nation that has survived bomb blasts in bazaars, coups in silence, floods that swallowed towns, and a thousand pinpricks of economic despair—war is not the monster under the bed. It is an old ghost, already named and mocked. This defence—sarcasm—is not new. The great cities of Lahore and Karachi, for all their grime and noise, hum with the knowing wit of café tables and tea shops. Jokes here are currency, traded faster than any rupee. It is how trauma is metabolised... South Asia, ever ancient, ever absurd, does not operate like the West’s neat dichotomies of war and peace. It operates in irony, in poetry, in the long memory of empires lost and futures dreamed…In Pakistan, humour is not escape. It is resistance.”

I unearth a rickety 30 second video I took of Lahore’s old city in 2018. It is night in the film and the city is vibrant. Live music is a rich, reverberating lull; palm trees glow red and violet with beautifying light; outdoor restaurants and shops flank the populous street; family encircles me; the minarets of the red sandstone Badshahi mosque looms, watches with its balcony eye. The camera swings, too fast, blurring the street in a 360 degree arc of music, light, glowing stone. But the film is too immersive for me to punish this amateur footage. I remember myself in this video, my naive invincibility and easy, undefined freedom. I was swaying, dancing, laughing, footsteps one with the melodic wind, untamed in my Lahore, city of my childhood, city of my dreams. The air smelled like heat, spices, smog, and maybe monsoon. I watch it on a loop till I fall asleep, counting prayer beads. ♦